The foundation of Saltaire

Welcome to this short talk on how Saltaire came to be created.

The Saltaire story does not start in Saltaire. It starts in Bradford – and our start date is 1800.

The Bradford economy in 1800 was a mixture of farming and manufacturing. The same as it had been for centuries.

Making cloth was the principal source of family income. Almost half the population earned their living from it – but production was almost entirely home-based.

Factories characterised the new world that was to be built.

And they used steam – not water – to power machinery.

In 1800, there was only one such ‘mill’ in Bradford. That was Holme Mill at the bottom of Thornton Road, only a 10 minute walk from where Bradford City Hall now stands.

This factory revolution took off… but slowly. By 1820, Bradford had 13 mills. Then things speeded up. By 1841, there were 67.

That almost doubled by 1851 when the figure jumped to 129. By 1874 there were 1,045 mills!

Over 1,000 mills needed a huge increase in factory workers, and in 1800, Bradford was tiny!

There were fewer than 14,000 people. So, Bradford had to grow, FAST, and it did. By 1850, it was 8 times bigger than in 1800. People migrated from Norfolk, Suffolk and Ireland to get paid work

But it doesn’t take a genius to realise that a place that grows this quickly will have problems. For a start, where were all these new workers going to live? Little wonder that, by the 1840s, the town was a really unpleasant and unhealthy place.

The air was grossly polluted.

Open water courses were polluted.

The average life expectancy was 18 years – many children died.

Housing conditions were appalling. One government report describes the accommodation of a woolcomber’s family:

They work in their one-room home – which is a cellar’. They had , a charcoal fire which is constantly burning by day – and frequently left smouldering at night. Eight people live and work in a space only 5m by 2m and only 2m high. In rainy weather, it is frequently flooded. Five people sleep in one bed – a man, his wife and his mother sleep in another.

Society in the town was on the brink of breakdown: at one point, Bradford was under military occupation!

In 1848, Salt was the mayor and used his position to tackle many of the town’s ills – but this was not a context in which his company could develop and prosper.

Nor was it ‘moral’, and Salt was a Congregationalist Christian who was hugely concerned about ‘morality’.

He believed that bad social conditions led to ‘immorality’. So, he decided to leave and stop running his business in Bradford.

Salt chose a rural area in the Aire valley, only 4 miles from Bradford. It would become Saltaire.

In Bradford, his business had been operating from at least 6 locations. By concentrating his works in one locality, in a single factory undertaking all aspects of textile production, he could take advantage of the large number of mechanical advances in textile production which had been brought about in recent decades.

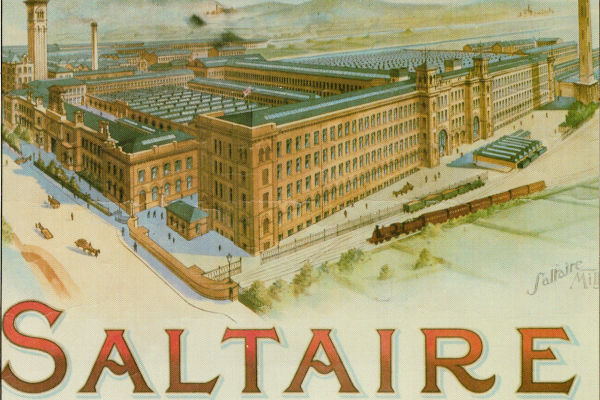

So, between 1851 and 1853, Salt built the biggest and most advanced factory in the world! It would employ 3,000 to 4,000 people and produce 27kms of cloth every day.

But this was not enough. The move into the country required a small town! At the dinner to celebrate the opening of the mill, a meal which fed his Bradford workforce, he said that

He hoped to draw around him a population that would enjoy the beauties of the neighbourhood, and who would be a well fed, contented, and happy body of operatives. He had given instructions to his architects that nothing should be spared to render the dwellings of the operatives a pattern to the country.

Because Titus Salt believed that bad social conditions led to ‘immorality’, it follows that he would believe that good social conditions promote good behaviour.

So, over the next 20 years, he built around 850 houses, AND shops, AND a school, AND two churches, AND a recreational and cultural hall, AND a hospital, AND alms-houses, AND allotments, AND a washhouse and baths, AND a park.

In Saltaire, we can see the work of a religious man who was also a capitalist. Like other Bradford masters, he employed children as young as 8 and took strong action during strikes by his workers. But unlike others, he believed that ‘doing the right thing’ was his religious duty and good business. He also wanted to leave work for his 5 sons.

Little wonder that Salt was widely regarded as the best master around. This was made clear when, after his death in 1876, his body was carried from his home in Brighouse to the family mausoleum in Saltaire.

It is said that 100,000 local people lined the route.